2 中国科学院大学, 北京100049

2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049

植物不同种群之间存在着广泛的竞争,这是形成不同尺度生态结构的重要因素(Fowler,1986;Casper and Jackson,1997;Tilman,1997;Raynaud and Leadley,2004;Fowler,2013)。自然生态系统另一个显著特征是区域内可同时生长多种物种,即具有生物多样性(Tilman et al.,1997;Adler et al.,2013)。如何解释自然生态系统植物种群间的竞争与共存是生态学研究的难题之一(Silvertown,2004;Doebeli and Ispolatov,2010;Kremer and Klausmeier,2013)。

植物不同种群间的竞争主要可分为资源竞争(主要是竞争土壤资源,如水、养分等)和空间竞争(光竞争)(Passarge and Huisman,2002)。在资源供给有限时,生态系统内主要表现为资源竞争;在资源供给充足时,系统主要表现为空间竞争(光竞争)。本文主要研究资源竞争。

现有的资源竞争理论最具代表的是莫诺模型,莫诺模型完全支持生态学上经典的“竞争排斥原理”(competitive exclusion principle),即在资源各向均匀分布的区域内,共存的物种种类数不超过供养其生长的资源种类数(Hardin,1960;MacArthur and Levins,1964;Levin,1970)。莫诺模型可以很好地解释浮游生物(Tilman,1977,1981;Tilman et al.,1981;Tilman and Sterner,1984;南春容和董双林,2003;南春容等,2003)和细菌(Hubbell,1980;南春容和董双林,2003;Yang and Jin,2010)的竞争过程,而难以解释自然生态系统不同植物种群间的竞争与共存(Loladze et al.,2004)。如全球分布着250000种维管束植物,全球有5种主要生物地理区域,每一种区域有大约50种不同的类型的生物群落,每一群落约有1000种植物(Fargione and Tilman,2002),而供养其生长的资源无非就是水、矿物质和养分等等。其竞争共存的物种种类数显然远远大于供养其生长的资源种类数。

为了解释上述“多样性悖论”(paradox of diversity),一些模型分别假设生态系统内部具有复杂的时间/空间结构,如生存/资源供给存在空间异质性(spatial heterogeneity)(Brandt et al.,2013;Schreiber and Killingback,2013;Shen et al.,2013;Ward et al.,2013)、种群具有不同的竞争与繁殖扩张策略(competition-colonization trade-off)(Nattrass et al.,2012;Usinowicz et al.,2012; Nagelkerke and Menken,2013)、资源供给率具有时间变率(temporal variability)(Letten et al.,2013;Shimadzu et al.,2013;Bulleri et al.,2014)和系统内具有3种以上营养级相互作用(interactions among three or more trophic levels)(Frean and Abraham,2001;Laird and Schamp,2006;Dammhahn and Kappeler,2014)等,在一定程度上可模拟局部多个种群共存的现象(Adler et al.,2013)。但是,产生生物多样性的本质机理仍无定论。

本文研究指出,即使不考虑上述假说,而仅根据植物自身生长特点引入“自抑制机制”,也可以使种群资源竞争产生稳定共存的结果。本文首先对经典的资源竞争模型(莫诺模型)进行了特性分析。然后结合自然生态系统植物自身的特性,将自抑制机制引入到莫诺模型中,建立自抑制资源竞争模型,并对其特性进行数学分析及数值模拟。最后探讨自抑制特性对自抑制资源竞争模型的重要性及下一步工作重点。

2 经典资源竞争模型(莫诺模型)

资源竞争模型主要用于描述一个生态系统内不同种群竞争资源(一般指非生物性资源)而生长的动力学过程,一般不考虑种群间的直接相互作用。经典资源竞争模型(莫诺模型)的动力学方程形式如下:

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}{N_i}}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = {G_i} - {M_i} = {N_i}{\mu _i}(R) - {N_i}{m_i}, i = 1,...,n $ | (1) |

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}R}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = S - LR - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{N_i}{\mu _i}(R){h_i}} , $ | (2) |

其中,${N_i}$表示物种i的种群密度;${M_i} = {N_i}{m_i}$表示物种i的死亡率,${m_i}$表示物种i的相对死亡率;R表示可利用资源(resource availability);${G_i} = {N_i}{\mu _i}(R)$表示物种i的生长率;${\mu _i}(R) = {\mu _{i\max }}R/(R + {R_{ih}})$称为莫诺函数,表示物种i的相对生长率,${\mu _{i\max }}$是${\mu _i}(R)$的上限值(当$R \to \infty $时),$0.5{\mu _{i\max }}$是相对生长率达$0.5{\mu _{i\max }}$时R的大小;S表示资源供给率;hi表示繁衍出单位数量物种i所需消耗的资源R;$\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{N_i}{\mu _i}(R){h_i}} $表示所有物种资源消耗率的总和;L表示相对资源自消耗率(specific resource loss rate),LR表示资源自消耗率(Passarge and Huisman,2002)。

由方程(1)可得,第i个物种的平衡条件是$R_i^{\rm{c}} = {m_i}{R_{ih}}/({\mu _i} - {m_i})$,$R_i^{\rm{c}}$称为临界可利用资源(critical resource availability)。当${R_i} \ge R_i^{\rm{c}}$时,${\rm{d}}{N_i}/{\rm{d}}t \ge 0$;当${R_i} < R_i^{\rm{c}}$时,${\rm{d}}{N_i}/{\rm{d}}t < 0$。当资源供给率S为常数(不随时间变化)时,模型的主要特性可表述为:

(1)如果系统中不同物种的$R_i^{\rm{c}}$都不相同,则平衡态仅是最小$R_i^{\rm{c}}$对应的物种存活,不存在多物种共存情况(Passarge and Huisman,2002);

(2)平衡态时可利用资源R不随资源供给率S变化;

(3)获胜物种不随资源供给率S的变化而改变。

3 考虑自抑制的资源竞争模型

3.1 模型方程

莫诺模型的主要不足是无法解释自然界高等植物种群之间竞争与共存的普遍现象。在一个自然植物生态系统中,共存的物种种类数远远大于供给其生长的资源种类数,如在热带雨林中每公顷约有400种树木(武吉华等,2004),这显然不能简单地用局部气候或环境差异来解释。另一方面,莫诺模型中优势物种(即竞争获胜的物种)不随资源供给率而变化,这显然无法再现自然生态系统随着气候分布格局而改变的特性,如随着降水量增加而从荒漠到灌丛/草原最终成为森林的变化过程。其根本原因是莫诺模型以浮游生物为原型,不考虑物种的个体大小,物种的生长率与自身种群密度成正比;而在植物生态系统中,随着物种个体大小/个体数增加,物种的生长率逐渐趋于饱和,即所谓的自抑制现象(Rees et al.,2010)。例如,树木的叶(生产器官)占个体总生物量的比例随个体增大而降低,因而相对生长率也降低;植物光合作用强度也随叶面积指数(即单位地表面积上的叶子总面积)上升而逐渐趋于饱和(Dickinson et al,2008)。为此,我们将自抑制特性引入资源竞争模型(莫诺模型)。为简单起见,取生长率随N的变化与随R的变化形式相同,即:

| $G = \delta (N) \times \mu (R) \propto \frac{{{\delta _{\max }}N}}{{N + {N_h}}} \times \frac{{{\mu _{\max }}R}}{{R + {R_h}}}. $ | (3) |

将(3)式引入莫诺模型(1)、(2),得到自抑制资源竞争模型:

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}{N_i}}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = {N_i}{g_i}(R,{N_i}) - {N_i}{m_i}, i = 1,...,n , $ | (4) |

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}R}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = S - LR - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{N_i}{g_i}(R,{N_i}){h_i}} , $ | (5) |

3.2 模型特性分析 3.2.1 单物种情形

方程(4)平衡态种群密度${\rm{d}}R/{\rm{d}}t = 0$满足:

| $N = \left\{ \begin{array}{l} (\frac{\phi }{m} \times \frac{R}{{R + {R_h}}} - 1){N_h} R > {R^*},\\ 0 R \le {R^*}, \end{array} \right.$ | (6) |

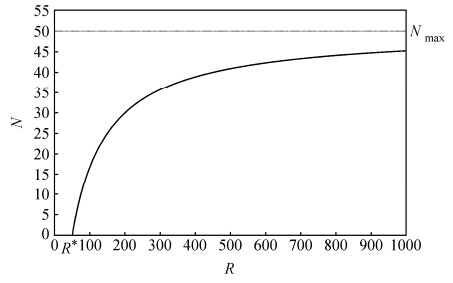

其中,${R^*} = {R_h}/(\phi /m - 1)$决定物种出现时(随着R变化)的最小R0。${N_{\max }} = (\phi /m - 1){N_h}$决定物种随R变化的上限值(图 1)。

| 图 1 N随R变化而变化的函数关系图。图中 Fig. 1 Variation of N as a function of R. |

同样令方程(5)中$i = 1$且${\rm{d}}R/{\rm{d}}t = 0$,得平衡态时可利用资源R:

| $R = (S + {N_h}mh - L{R_h} - {N_h}\phi h + \sqrt {{{(S + {N_h}mh - L{R_h} - {N_h}\phi h)}^2} + 4L(S + {N_h}mh)} {\rm{ }})/2L $ | (7) |

由(6)式、(7)式知平衡态时种群密度N直接决定于可利用资源R,平衡态时可利用资源R直接决定于资源供给率S;且N与R和N与S均正相关。

3.2.2 多物种情形 3.2.2.1 模型性质一该模型第一条性质是多物种可以稳定共存,分析如下:

令公式(4)${\rm{d}}{N_i}/{\rm{d}}t = 0$,且记${\lambda _i}{\rm{ = }}{\phi _i}/{m_i}$,$R_i^* = {R_{ih}}({\lambda _i} - 1)$,则

| ${N_i} = \left\{ \begin{array}{l} (\frac{{{\lambda _i}R}}{{R + {R_{ih}}}} - 1){N_{ih}} R > R_i^*\\ 0 R \le R_i^* \end{array} \right.$ | (8) |

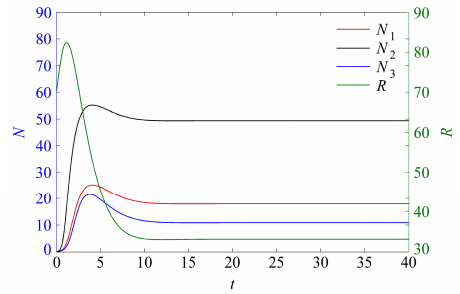

因为当$R > R_i^*$时,平衡态物种i的种群密度${N_i}$不为${N_i}$,由于n的任意性且i可以取遍$1,2,...,n$,所以说这n种物种是稳定共存的(图 2)。令公式${\rm{d}}R/{\rm{d}}t = 0$,且结合(8)式得到平衡态R的表达式和N没有关系,故不影响多物种稳定共存的性质。

| 图 2 当n=3时,模型(4)、(5)的数值解:三物种稳定共存 Fig. 2 The numerical simulation results in models(4) and (5)when n=3: Stable coexistence in three species |

该模型的第二条性质:物种随R的变化可以依次出现优势物种,竞争不改变每一个物种的$N - R$曲线。

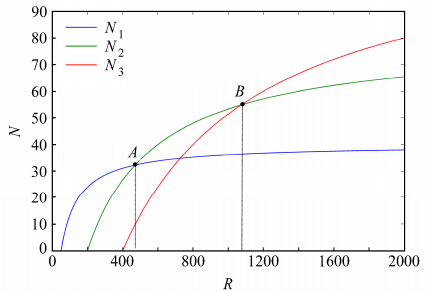

由3.2.1单物种情形分析知$R_i^* = {R_{ih}}/({\lambda _i} - 1)$决定物种i出现时的最小R,${N_{i\max }} = ({\lambda _i} - 1){N_{ih}}$决定物种i随R变化的上限值;故若满足$R_1^* < R_2^* < ... < R_n^*$且${N_{1\max }} < {N_{2\max }} < ... < {N_{n\max }}$时,会出现优势物种更替的情形(图 3,具体参数及数值见表 1)。另外由(8)式知(4)式、(5)式中n增加或减少,不会影响每个物种i的$N - R$曲线,即竞争不改变每一个物种的$N - R$曲线(图 3)。

| 图 3 平衡态三物种种群密度随可利用资源R变化关系 Fig. 3 Population densitity changes with resource availability R in equilibrium when n=3 |

|

|

表 1 当n=3时,模型(4)、(5)的数值解使用的参数和初值 Table 1 Detail parameters and initial values of numerical simulation results in models(4) and (5)when n=3 |

图 3是n取值为3时,自抑制资源竞争模型平衡态物种种群密度随可利用资源R的变化关系。图中物种1、物种2和物种3分别在R=50、R=200和R=400时出现,物种1在A点之前为优势物种,物种2在A点和B点之间时为优势物种,物种3在B点之后为优势物种;这是因为三物种满足:$R_1^* < R_2^* < R_3^*$且${N_{1\max }} < {N_{2\max }} < {N_{3\max }}$。若从这三物种中去掉物种1或增加一种物种4,物种2、3或物种1、2、3的$N - R$曲线不会发生变化。

3.2.2.3 模型性质三

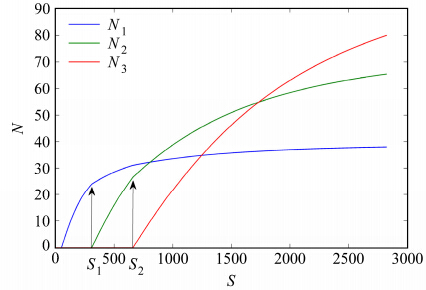

该模型的第三条性质:物种随S的变化可以依次出现优势物种,每一物种出现时前一物种的$N - S$曲线会出现转折点(图 4)。

| 图 4 平衡态三物种种群密度随资源供给率S变化关系 Fig. 4 Population density changes with resource supply rate S in equilibrium |

令公式(5)中${\rm{d}}R/{\rm{d}}t = 0$,得到$S = LR + \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{N_i}{g_i}(R,{N_i}){h_i}} $ ,其中${N_i}$依赖于R [公式(8)]。显然S与R成正相关,故$N - S$曲线与$N - R$曲线基本相似;但每一物种出现时,S-R曲线会出现转折点,从而导致前一物种的$N - S$曲线会出现转折点。特性c可以描述自然生态系统随着气候分布格局而改变的特性。

图 4是n取值为3时,自抑制资源竞争模型平衡态物种种群密度随资源供给率S的变化关系。在S1处物种2出现时,物种1的$N - S$曲线出现转折点;在S1处物种3出现时,物种2的$N - S$曲线出现转折点。

3.2.2.4 多物种稳定共存原因分析

令方程(4)中dNi/dt=0得到第i个物种的平衡条件是$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*} = {R_{ih}}/[{\lambda _i}{N_{ih}}/({N_i} + {N_{ih}}) - 1]$,同样称$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*}$为模型(4)、(5)的临界可利用资源。

取(4)、(5)中任意两物种A、B来分析,不妨假设初始状态满足$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}} < R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}} < R$,那么${N_{\rm{A}}}$、${N_{\rm{B}}}$都将增加,而${N_{\rm{A}}}$、${N_{\rm{B}}}$的增加会消耗资源R,使R减少;同时${R^{{\rm{c}}*}}$是${N_i}$的单调递增函数,故${N_{\rm{A}}}$、${N_{\rm{B}}}$的增加会使$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$、$R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$增加;这两种因素最终会使R处于状态:$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}} < R < R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$,此时,${N_{\rm{A}}}$将增加,${N_{\rm{B}}}$将减少。同样因为$R_{}^{{\rm{c*}}}$是${N_i}$的单调递增函数,所以${N_{\rm{A}}}$增加会使$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$增大,${N_{\rm{B}}}$减少会使$R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$减小;因此,$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}} < R < R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$这种状态会因为$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$的增大和$R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$的减小最终变为:$R_{\rm{A}}^{{\rm{c*}}} = R = R_{\rm{B}}^{{\rm{c*}}}$,此时${N_{\rm{A}}}$、${N_{\rm{B}}}$将不增不减,物种A、B将稳定共存。

这种结果很容易推广到n种物种的情形:不论初始状态R与$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*}(i = 1,2,...,n)$的大小关系如何,只要R与$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*}(i = 1,2,...,n)$有所不同,那么就会导致每一物种i的Ni发生变化,Ni的变化进而会使物种i的特征参数$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*}(i = 1,2,...,n)$以及R趋于相同,$R_i^{{\rm{c}}*}(i = 1,2,...,n)$与R相同就意味着这n物种将稳定共存。

4 结论和讨论本文模型与莫诺模型的本质差异在于,莫诺模型中各物种生存的临界可利用资源Rc是恒定的,不随物种种群密度N及资源供给率S而发生变化,因而各物种对资源的竞争能力不变,仅有Rc最小的物种可以存活,不能达到多物种共存;而本文模型通过引入生长的自抑制,使得临界可利用资源随物种种群密度增加而上升,资源竞争的结果使得各物种的Rc*达到动态平衡,从而实现多物种共存,同时可再现生态系统中优势物种随资源供给率变化的现象。

自抑制是自然生态系统的重要现象。许多生态学理论与模型认为,种内竞争(即自抑制)大于种间竞争(互抑制)是使物种稳定共存的重要因素(Chesson,2000;Zhang,2003)。这些理论一般适用于种群间存在直接竞争的情况(如光竞争)。本文研究表明,即使在不考虑直接竞争的情况,如在土壤资源(如水、养分)供给不足而限制植物生长的生态系统中,同样需要引入自抑制以实现生态系统内的稳定共存。其实,生态系统中一个物种/群体生长常具有一定聚集性,即使当生态系统内部个体分布相对稀疏(因而可忽略互抑制)时,依然在一定程度上存在自抑制。

资源竞争与光竞争的一个重要区别在于,资源是可分配的,并在一定空间尺度上可近似假设为均匀分布,如公式(4)中不同物种具有相同的可利用资源,因而物种状态(种群密度)随资源供给率增加而单调上升。而当资源供给充足时,生态系统内主要表现为对空间/光的竞争,高大植物(如树)可更有效地获取阳光,并通过遮荫抑制低矮植物生长,即光(强度)的分配是不均匀的(Weissing and Huisman,1994;Huisman and Weissing,1994)。我们下一步工作将光竞争引入自抑制资源竞争模 型,期望模拟不同物种随资源供给率的增大依次出现、达到最大值并逐渐消亡的现象。

| [1] | Adler P B, Fajardo A, Kleinhesselink A R, et al. 2013. Trait-based tests of coexistence mechanisms [J]. Ecology Letters, 16 (10): 1294-1306. |

| [2] | Brandt A J, Kroon H, Reynolds H L, et al. 2013. Soil heterogeneity generated by plant-soil feedbacks has implications for species recruitment and coexistence [J]. Journal of Ecology, 101 (2): 277-286. |

| [3] | Bulleri F, Xiao S, Maggi E, et al. 2014. Intensity and temporal variability as components of stress gradients: implications for the balance between competition and facilitation [J]. Oikos, 123 (1): 47-55. |

| [4] | Casper B B, Jackson R B. 1997. Plant competition underground[J]. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 28(1): 545-570. |

| [5] | Chesson P. 2000. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity[J]. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 31 (1): 343-366. |

| [6] | Dammhahn M, Kappeler P M. 2014. Stable isotope analyses reveal dense trophic species packing and clear niche differentiation in a malagasy primate community [J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 153 (2): 249-259. |

| [7] | Dickinson R E, Tian Y H, Liu Q, et al. 2008. Dynamics of leaf area for climate and weather models[J]. J. Geophys. Res., 113, D16115. |

| [8] | Doebeli M, Ispolatov I. 2010. Complexity and diversity [J]. Science, 328 (5977): 494-497. |

| [9] | Fargione J, Tilman D. 2002. Competition and Coexistence in Terrestrial Plants [M].// Sommer U, Worm B. Competition and Coexistence. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 165-206. |

| [10] | Fowler M S. 2013. The form of direct interspecific competition modifies secondary extinction patterns in multi-trophic food webs [J]. Oikos, 122 (12): 1730-1738. |

| [11] | Fowler N L. 1986. The role of competition in plant communities in arid and semiarid regions [J]. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 17 (1): 89-110. |

| [12] | Frean M, Abraham E R. 2001. Rock-scissors-paper and the survival of the weakest [J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 268 (1474): 1323-1327. |

| [13] | Hardin G. 1960. The competitive exclusion principle [J]. Science, 131 (3409): 1292-1297. |

| [14] | Hubbell S P. 1980. Single-nutrient microbial competition: Qualitative agreement between experimental and theoretically forecast outcomes [J]. Science, 207 (4438): 1491-1493. |

| [15] | Huisman J, Weissing F J. 1994. Light-limited growth and competition for light in well-mixed aquatic environments: an elementary model [J]. Ecology, 75 (2): 507-520. |

| [16] | Kremer C T, Klausmeier C A. 2013. Coexistence in a variable environment: Eco-evolutionary perspectives [J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 339: 14-15. |

| [17] | Laird R A, Schamp B S. 2006. Competitive intransitivity promotes species coexistence [J]. The American Naturalist, 168 (2): 182-193. |

| [18] | Letten A D, Ashcroft M B, Keith D A, et al. 2013. The importance of temporal climate variability for spatial patterns in plant diversity [J]. Ecography, 36 (12): 1341-1349. |

| [19] | Levin S A. 1970. Community equilibria and stability, and an extension of the competitive exclusion principle [J]. American Naturalist, 104 (939): 413-423. |

| [20] | Loladze I, Kuang Y, Elser J J, et al. 2004. Competition and stoichiometry: Coexistence of two predators on one prey [J]. Theoretical Population Biology, 65 (1): 1-15. |

| [21] | MacArthur R, Levins R. 1964. Competition, habitat selection, and character displacement in a patchy environment[J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 51 (6): 1207. |

| [22] | Nagelkerke C J, Menken S B J. 2013. Coexistence of habitat specialists and generalists in metapopulation models of multiple-habitat landscapes [J]. Acta Biotheoretica, 61 (4): 467-480. |

| [23] | 南春容, 董双林. 2003. 资源竞争理论及其研究进展 [J]. 生态学杂志, 22 (2): 36-42. Nan Chunrong, Dong Shuanglin. 2003. A review on resource competition theory [J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology (in Chinese), 22 (2): 36-42. |

| [24] | 南春容, 董双林, 金秋. 2003. 磷限制下大型海藻与微藻间资源竞争理论的实验验证 [J]. 植物学报, 45 (3): 282-288. Nan Chunrong, Dong Shuanglin, Jin Qiu. 2003. Test of resource competition theory between microalga and macroalga under phosphate limitation [J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology (in Chinese), 45 (3): 282-288. |

| [25] | Nattrass S, Baigent S, Murrell D J. 2012. Quantifying the likelihood of co-existence for communities with asymmetric competition[J]. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 74 (10): 2315-2338. |

| [26] | Passarge J, Huisman J. 2002. Competition in well-mixed habitats: From competitive exclusion to competitive chaos [M].// Sommer U, Worm B. competition and Coexistence. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 7-42. |

| [27] | Raynaud X, Leadley P W. 2004. Soil characteristics play a key role in modeling nutrient competition in plant communities [J]. Ecology, 85 (8): 2200-2214. |

| [28] | Rees M, Osborne C P, Woodward F I, et al. 2010. Partitioning the components of relative growth rate: how important is plant size variation? [J]. The American Naturalist, 176 (6): E152-E161. |

| [29] | Schreiber S J, Killingback T P. 2013. Spatial heterogeneity promotes coexistence of rock-paper-scissors metacommunities [J]. Theoretical Population Biology, 86: 1-11. |

| [30] | Shen G C, He F L, Waagepetersen R, et al. 2013. Quantifying effects of habitat heterogeneity and other clustering processes on spatial distributions of tree species [J]. Ecology, 94 (11): 2436-2443. |

| [31] | Shimadzu H, Dornelas M, Henderson P A, et al. 2013. Diversity is maintained by seasonal variation in species abundance [J]. BMC Biology, 11 (1): 98. |

| [32] | Silvertown J. 2004. Plant coexistence and the niche [J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19 (11): 605-611. |

| [33] | Tilman D. 1977. Resource competition between plankton algae: An experimental and theoretical approach [J]. Ecology, 58 (2): 338-348. |

| [34] | Tilman D. 1981. Tests of resource competition theory using four species of Lake Michigan algae [J]. Ecology, 62 (3): 802-815. |

| [35] | Tilman D. 1997. Mechanisms of plant competition [M].// Crawlay M J. Plant Ecology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 239-261. |

| [36] | Tilman D, Sterner R W. 1984. Invasions of equilibria: Tests of resource competition using two species of algae [J]. Oecologia, 61 (2): 197-200. |

| [37] | Tilman D, Mattson M, Langer S. 1981. Competition and nutrient kinetics along a temperature gradient: An experimental test of a mechanistic approach to niche theory [J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 26 (6): 1020-1033. |

| [38] | Tilman D, Lehman C L, Thomson K T. 1997. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: Theoretical considerations [J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 94 (5): 1857-1861. |

| [39] | Usinowicz J, Wright S J, Ives A R. 2012. Coexistence in tropical forests through asynchronous variation in annual seed production [J]. Ecology, 93 (9): 2073-2084. |

| [40] | Ward D, Wiegand K, Getzin S. 2013. Walter's two-layer hypothesis revisited: back to the roots! [J]. Oecologia, 172 (3): 617-630. |

| [41] | Weissing F J, Huisman J. 1994. Growth and competition in a light gradient [J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 168 (3): 323-336. |

| [42] | 武吉华, 张绅, 江源, 等. 2004. 植物地理学 [M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 257-262. Wu Jihua, Zhang Shen, Jiang Yuan, et al. 2004. Plant Geography (in Chinese) [M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 257-262. |

| [43] | Yang S W, Jin X C. 2010. Resource competition of Cyanobacteria, Chlorococcalesa and diatoms for ammonium ions under steady and non-steady state [J]. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 43 (4): 364-376. |

| [44] | Zhang Z B. 2003. Mutualism or cooperation among competitors promotes coexistence and competitive ability [J]. Ecological Modelling, 164 (2-3): 271-282. |

2015, Vol. 20

2015, Vol. 20